The Washington Post hired Michael Gerson, presumably, to do what Michael Gerson does best. In today's op-ed, that's to make something out of nothing, and that something happens to be pretty big: Gerson attempts to reframe the mystique surrounding the new president. Instead of being the postpartisan candidate presented during campaign season, Gerson argues that Obama is the most partisan president--in recent* history.

Gerson's tack is two pronged. First, seize on a piece of evidence that reflects an ongoing trend in American politics, the stubborn and intractable calcification of political party affiliation allegiance--more on this awkward phrase in a second--and sharply wield said evidence. Second, leave out some important details.

The evidence in question is an article from the Pew Research Center based on a bit of recent polling. The Pew lede actually jumps the shark, as revealed by the final paragraph. First the alpha: "For all of his hopes about bipartisanship, Barack Obama has the most polarized early job approval ratings of any president in the past four decades."

Mighty. Bold. One can see the temptation to saddle this horse and ride, as Gerson does. But much more telling--and left out of Gerson's piece--is this nugget buried toward the very end, the omega: "The growing partisan divide in presidential approval ratings is part of a long-term trend."

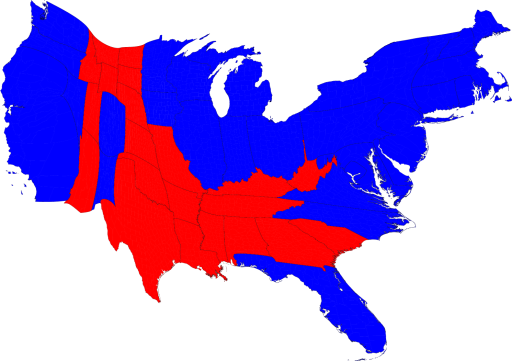

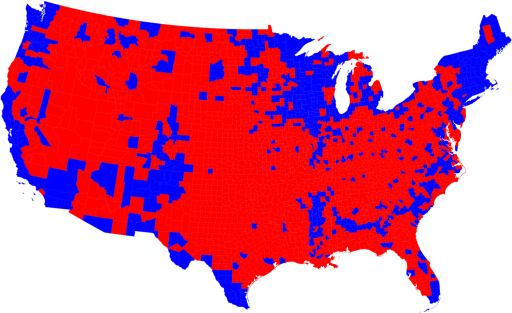

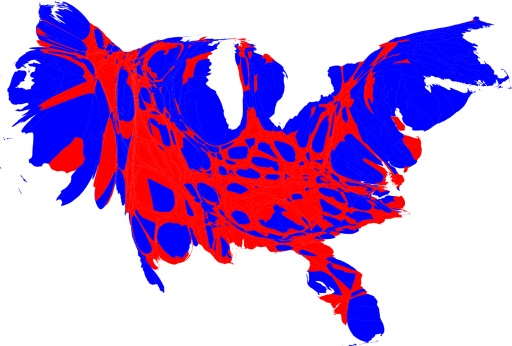

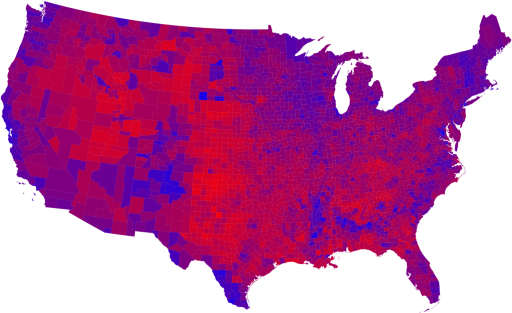

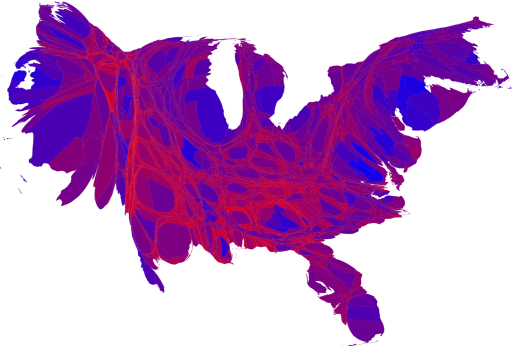

Or call it a yin and a yang phenomenon. Whatever. The latter grab from the article balances and contextualizes the opening quote in a way that might just be essential to understanding Pew's data. It's not that Obama himself is the most polarizing president. The electorate, however, is at its most polarized in history when evaluating the 44th president's early success.

There's a subtle and absolute difference in the semantics here. On the one hand (Gerson's), Obama is a catalyzing figure. On the other, partisanship itself catalyzes the public to opine favorably. That trend is relatively new. Indeed, Pew's brief article explores the evolution of partisanship and early presidential approval ratings in recent decades.

Going back in time, partisanship was far less evident in the early job approval ratings for both Jimmy Carter and Richard Nixon. In fact, a majority of Republicans (56%) approved of Carter's job performance in late March 1977, and a majority of Democrats (55%) approved of Nixon's performance at a comparable point in his first term.

So far, so good. Voters are willing to give a president of the opposite party the benefit of the doubt, at least in the early term. But over time, Pew goes on, this trend has receded from the landscape. Gerson alludes to this data without catching its significance. Pew includes a historical context by which we should understand Pew's findings, but Gerson glosses that over. Which brings me to the awkward and apt phrase "stubborn and intractable calcification of political party affiliation allegiance."

To unpack just a little, this is not to say that more Americans are more affiliated than ever. The opposite, I think, begins to look true when we consider some more of Pew's numbers. In

findings out just last month, Pew sees the Republican party enjoying less support today than in either of the two previous election cycles, and less even than in Pew's 16 years of polling.

In 5,566 interviews with registered voters conducted by the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press during the first two months of 2008, 36% identify themselves as Democrats, and just 27% as Republicans.

The share of voters who call themselves Republicans has declined by six points since 2004, and represents, on an annualized basis, the lowest percentage of self-identified Republican voters in 16 years of polling by the Center.

The Democratic Party has also built a substantial edge among independent voters. Of the 37% who claim no party identification, 15% lean Democratic, 10% lean Republican, and 12% have no leaning either way.

Fewer voters identify with the Republican party today than at any point in the last 16 years. And this is where "affiliation allegiance" comes in, evidenced on both sides of the partisan divide. As the minority party, the Republican phenomenon is more stark today than its Dem counterpart. As the numbers of self-identified Republicans dwindle, the remaining loyalists become louder. Those left become more strident. As the big tent empties, the remaining voices echo in the void, and echo vociferously. This is the allegiance to which I refer: volume.

Consider the politics of failure. The GOP leadership has consigned itself to arguing about whether it's acceptable to root for the failure of the president, or just the president's policies, in a time of arguable economic catastrophe. This is not a party demonstrating reasonable debate but pure obstructionism. Gerson cites the recent budget vote as evidence of Obama's failure to get beyond partisanship, but ignores the fact that Republicans in Congress have committed themselves to an agenda of obstruction from day one.

And the American public has taken note!Where's John Wayne in this Republican party? "I didn't vote for him, but he's my president and I hope he does a good job." That's Wayne in

response to the election of JFK in 1960. We're not hearing such highbrow sentiment these days. Instead we get Rush Limbaugh calling for

failure, and the Republican leadership falling over itself to

justify the same sentiment.

In that context, it's easier to understand how Gerson can write "It is a sad, unnecessary shame that Barack Obama, the candidate of unity, has so quickly become another source of division." The writer uses superficial data corresponding to approval ratings to illustrate how divisive a President Obama is to this country. But Gerson leaves out the relevant context to understand that data, and so becomes merely one more strident voice in a big, empty tent.

*Added after publication--Ed.